A Python Tkinter GUI App That Won't Make You Puke Blood (Part 1)

Buliding a Pure Python / Tkinter application for downloading from FormSG (Part 1)

Source: Jon Tyson (https://unsplash.com/photos/Q_GnkCF1PrE)

Source: Jon Tyson (https://unsplash.com/photos/Q_GnkCF1PrE)

If you are looking to build simple GUI application in Python Tkinter and distribute it to your friends, but are having problems navigating the greek documentation, look no further, read on for how I did it.

TL;DR

GUI applications are a good way to share tools that you have built with non-technical friends / colleagues. And in Python, the standard library contains Tkinter ("Tk interface") for building GUI applications.

Documentation for Tkinter may be hard to navigate at first, it is recommended to consult the following resources (and in the specific order): Tkinter Life Preserver, TkDocs, effbot.org, Tcl/Tk documentation.

Background

As part of Covid-19 response, I was involved in collecting information via a government website called FormSG. I was administering over 20 forms, with multiple versions of each form, and needed to do daily reporting.

-

In short, there was a lot of manual work involved and naturally, I automated the task using Selenium.

However, while I am comfortable running the automation script from commandline, I needed a way to share the tool with my colleague. And that's when I started taking a closer look at Tkinter. (Note: I initially shared the scripts used batch files, and taught my colleague how to the batch files.)

Navigating the Sea of Tkinter Resources

Tkinter is part of Python's standard library, providing access to the Tcl/Tk graphical user interface toolkit. And since Python's standard library has always been of very high standard, with well-thought out inclusion / exclusion and implementation, it must say something that Tcl/Tk is the chosen GUI framework.

Unfortunately, documentation for Tcl/Tk (the underlying framework) and Tkinter (Python's wrapper to the framework) are hard to follow at times.

Having built this GUI application, these are the resources (in order of priority) I would recommend:

-

If you are new to Tkinter, refer to the Tkinter Life Preserver page on Python's official documentation for a good overview on how to approach using Tkinter. (E.g., It suggests first understanding how Tcl/Tk works, before looking at Tkinter, which is an wrapper around Tcl/Tk.)

-

Next, when selecting, laying out, and specifying the behaviors of widgets (i.e., things like text boxes and buttons), refer to TkDocs for clear explanation, good coverage of topics, and good code samples.

-

If the information is still not available, refer to effbot.org (which covers certain things not covered by TkDocs).

-

Finally, if the feature is not covered by either of the above, refer to Tcl/Tk documentation for the official specification, and use the knowledge from the Tkinter Life Preserver to translate those into Tkinter methods.

General Design of The GUI Application

(Note: I've skipped the basics on how to bootstrap a Tkinter app, you can refer to the Hello World example from Tkinter Life Preserver.)

For my simple application, I conceptually divided the components into three:

-

state

-

widgets

-

and event handlers (AKA actions).

These correspond roughly to the model, view and controller in the traditional MVC framework.

State

I initialize the state in the __init__() method of my App class as follows:

class App:

def __init__(self, master, menu=None):

...

# Data

self.chrome_driver_path = tk.StringVar()

self.download_path = tk.StringVar()

self.forms = OrderedDict()

self.form_name = tk.StringVar()

self.form_id = tk.StringVar()

self.form_secret_key = tk.StringVar()

self.email = tk.StringVar()

self.one_time_password = tk.StringVar()

...

Notice the use of tk.StringVar() to create the variables; this is necessary

for two-way communication with the widgets that will be displaying the data,

or accepting input for the data.

Widgets

I created a mini-DSL using namedtuple and a simple loop, so that the

widget-related code may be written in a more declarative-like way.

-

So instead of using multiple method calls to instantiate one widget:

widgets['frame_config'] = ttk.LabelFrame('text': 'Step 0: Configuration') widgets['frame_config'].grid('column': 0, 'row': 0, 'padx', 10, 'pady': 10) -

I can simple declare the widget, and pass the list of

Widgetto a loop for actual instantiation:Widget('frame_config', ttk.LabelFrame, {'text': 'Step 0: Configuration'}, 'grid', {'column': 0, 'row': 0, 'padx': 10, 'pady': 10})

To achieve the above, we need to define a namedtuple as follows:

Widget = namedtuple('Widget', 'name type options geometry_manager geometry_options',

defaults=[{}, 'pack', {}])-

If you are not familiar with

namedtuple, it is part of Python's standard library, and allows creation of simple "value classes" whose members may be accessed via the dot operator. -

In the code fragment above, it defines a new "class" named

Widget, that I can "instantiate" by callingWidget(), passing in as arguments values for each of the fields, which have the following meaning:Field Name Meaning namename of the widget, serving as identifier typetype of the widget, e.g., ttk.Entry for a usual text input optionsarguments for the widget constructor, e.g., ttk.Entry(options)geometry_managerone of the three geometry managers in Tk: place, pack or grid geometry_optionsarugments for the geometry manager method, e.g. .pack(options)

In addition to the namedtuple, we need to initialize the widgets using the

following loop:

WIDGETS = [...] # List of Widget

for name, widget_type, options, geometry_manager, geometry_options in WIDGETS:

parent = options.pop('parent', None)

parent_widget = self.widgets.get(parent, master) # Parent defaults to master

w = widget_type(parent_widget, **options)

getattr(w, geometry_manager)(**geometry_options)

self.widgets[name] = w-

One other major benefit of using the loop is that it allows us to use a dictionary to hold all the widgets behind-the-scene implicitly/, and refer to each element by its name given in the

Widget()call, instead of using dictionary access. -

As such, is now trivial to reposition widgets within the hierarchy: within the

optionsdictionary passed to theWidget()call, just change the value of"parent"to the name of the relevant parent widget. -

If the default approach is used instead, reference to each widget either must be kept as separate instance member on the

Appinstance, or (if a dictionary is used) there would be explicit dictionary access littered throughout the code, making it very clunky.

Progress So Far

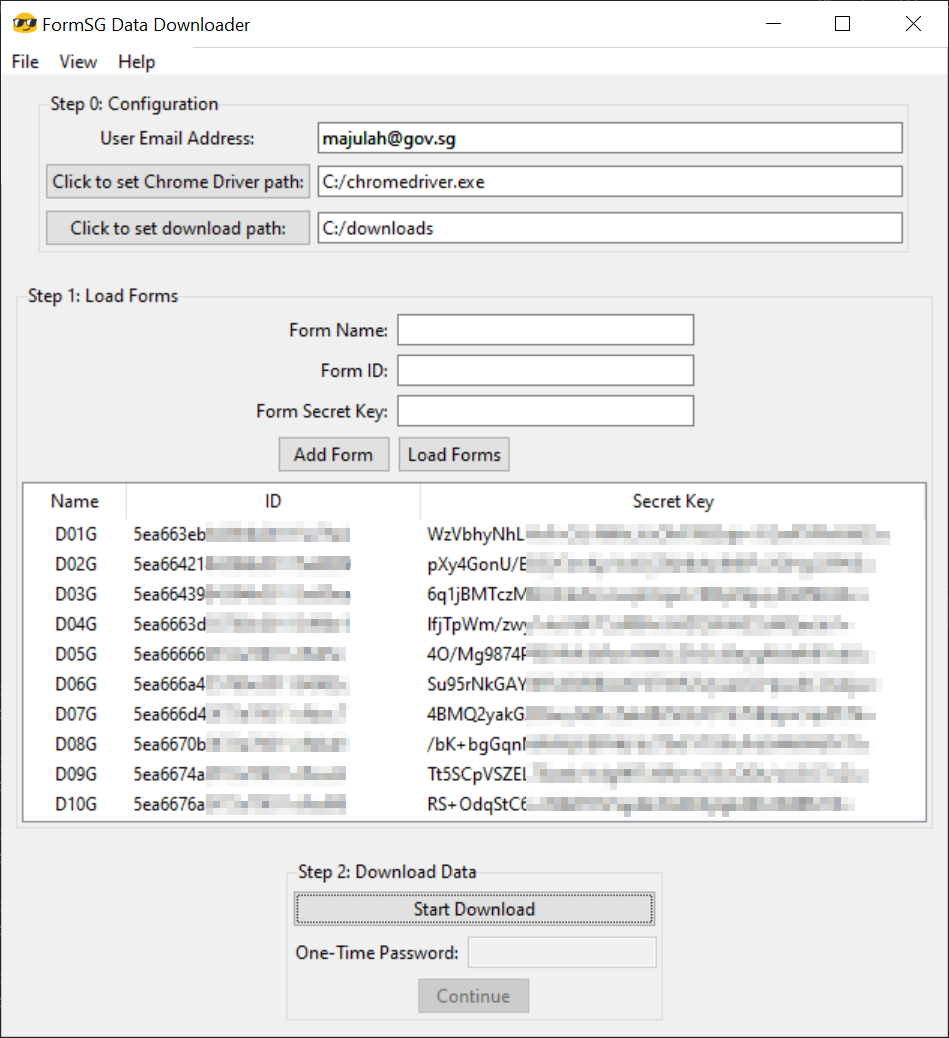

With the mini-DSL in place, it is sufficiently simple to declare the layout to get something like this:

In the next part, I'll cover how I added the event handlers (including a brief foray into asynchronous GUI programming), and hopefully the releasing and packaging of the application.

Lessons Learnt

Don't be afraid to design your own mini-language if it makes your life simpler, especially for a side project.